The OWC Thunderbay 4: a photographer's storage solution

Probably one of the least sexy yet most critical parts of creating any sort of photography or videography is storage. The need for a good storage solution isn’t immediate, but as we accumulate more and more photo and video content, the lack of a strong solution can really sneak up on you and bite you in the ass.

My primary photo storage was probably similar to most of you: external portable hard drives. An obvious solution at first - they’re cheap, common, and easy to use. A plug-and-play solution. Run out of space on your external drive? Easy, just get another one and keep going.

The old solution.

But what happens after a few years when you’ve amassed terabytes of photos and videos? Next thing you know, you’ve got a mess of hard drives everywhere, and you’re always swapping them or even losing (!) them. You’ve fallen into the nightmare of hard drive hell. This is what happened to me. I had to dig myself out of this hole.

After some research I decided my solution needed four things:

Capacity: From the past year alone I have over 3 terabytes of photography, and about a terabyte of video footage as well. I needed something that can easily last for 4-5 years without having to think about it. Scalability is a plus.

Speed: A normal portable hard drive has read and write speeds of around 100 megabytes per second. This works ok for basic photo work, but when you’re working with massive photo libraries and big imports it will slow you down. And video editing is a no-go, especially with big 4K video files.

Robustness: Let’s be honest - we need to think of spinning hard drives as a consumable product. All hard drives will fail. That’s just the nature of having a little disk spinning in circles 7200 times a minute. And when they fail, you can lose years of your past work. I wanted something a little more robust that can stand up to the chance of disk failures.

Note - this blog post doesn’t go into backing up your data or any backup solutions I use. We will save that for another blog post, but for now just know to BACK. UP. YOUR. SHIT.

Elegance: This is probably the most important one for me. I wanted something simple and not in need of constant tinkering, something that just runs in the background, out of sight, out of mind.

The OWC Thunderbay 4

Enter the OWC Thunderbay 4.

The Thunderbay 4, in essence, is a metal box with a bunch of (four, actually) hard drives in it. It’s available with a variety of different hard drive configurations or as an empty enclosure into which you can load your own drives. I opted for the enclosure and filled it with four 8TB Seagate IronWolf NAS Drives, for a total of 32TB of storage (kind of - we’ll get to that in a second). This should easily last me several years worth of photo and video. Capacity, check.

Note: Opting to add your own drives means that the Thunderbay enclosure will have to certify them when setting it up - a process that can take a couple of days depending on the size of the drives.

It connects to my computer via Thunderbolt 3, which is capable of transferring five gigabytes of data per second. The cool thing about Thunderbolt is that it has such a high transfer rate that you can actually daisy chain additional accessories - you could potentially have several Thunderbay units all plugged into each other connected to your computer with a single cable. Also, you can charge your laptop with this one cable. Pretty neat.

I filled this Thunderbay 4 enclosure with four 8TB Seagate IronWolf drives.

The benefit of having four hard drives in a single enclosure is that the drives can interact with each other with RAID - a system of drive redundancy. Without getting too deep into the weeds, RAID will sacrifice some of your total capacity to store data about what is on all of the other drives, so when (remember, its a matter of when, not if) a hard drive fails and is replaced, the data from the other three drives will be used to rebuild everything that was stored on the failed drive. It’s like a safety net for drive failure. Robustness, check.

Note: RAID is not a substitute for a proper back up! Should something happen to the Thunderbay, as opposed to just a single drive, there is still a risk of total data loss.

For my particular case, I decided to go for a RAID setting known as RAID 5 - this means that one hard drive’s worth of storage will be used across the four drives for redundancy purposes. As a result, I am left with 24TB of usable storage out of 32TB of total storage. It’s a fair price to pay for redundancy.

Speed test results: 480MB/s write, 690MB/s read

Another benefit of RAID is speed. Since the four drives are working together, data can be read from all four drives at once, leading to some big speed gains depending on the RAID level. With the RAID 5 setting that I chose, I can get around 480 megabytes per second write speed, and almost 700 megabytes per second read speed. Not bad! That’s as good as a lot of SSDs out there, and way faster than using a portable hard drive. Browsing through my Lightroom catalog is a breeze, and big imports are a non-factor. It’s plenty fast for editing 4K video directly off of the drive as well. No need for a solid state working drive. Speed, check.

So RAID is great and all, but how is it run and set up? There are two ways this is done. The first is through hardware RAID, meaning that the RAID controller is built right into the hard drive enclosure. This can often be quite expensive. The Thunderbay uses the other kind - software RAID. This means that the RAID is controlled using software that runs in the background on your computer. This was problematic with older computers as it ate into the computer’s performance, but with modern computers the effect isn’t noticeable.

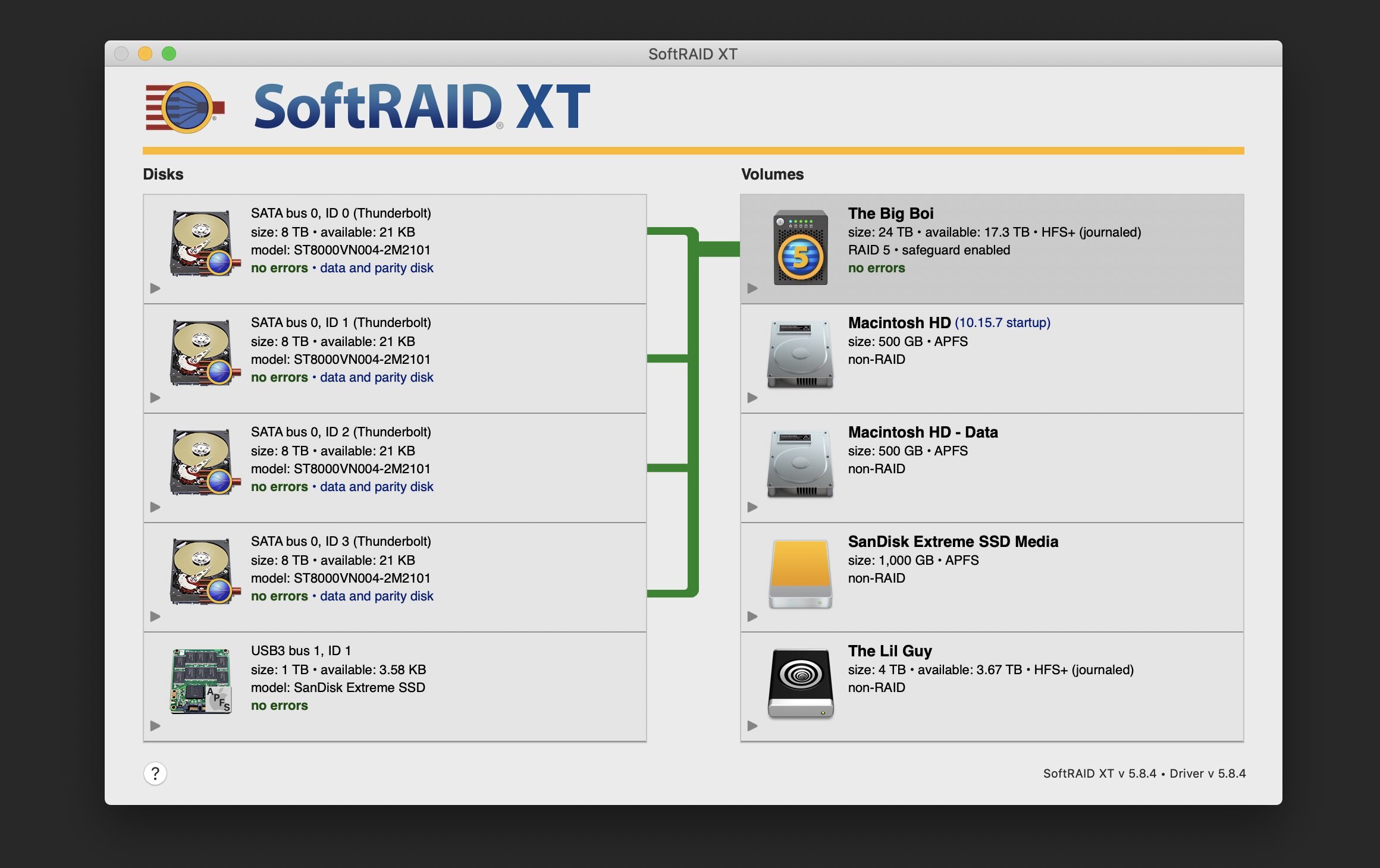

The software that the Thunderbay uses is called SoftRAID. It looks a little confusing to use at first, but if you follow the instructions it’s straightforward and easy to configure. Plus, once you set it up you really have no need to touch it until a drive fails (in which case SoftRAID supposedly gives you plenty of advance warning - something I have yet to experience since I haven’t had any failures yet).

The OWC SoftRAID interface looks complex but in use it’s pretty straightforward.

Overall my experience using the Thunderbay has so far been fantastic. I now have plenty of breathing room when it comes to storage, and the speed increase has had a noticeable effect on both my photo editing in Lightroom and editing in Final Cut Pro. Everything lives on the drive and can easily be accessed and edited when I need to without having to fiddle with additional hard drives. I don’t even have to think about it. Elegance, check.

That’s not to say that the Thunderbay is totally perfect - no product ever is. There are a couple of downsides I’ve encountered so far:

The four high speed hard drives can make some noise but as far as I can tell the cooling fan is near-silent.

Noise: This thing can actually get pretty loud. Most of the noise seems to come from the hard drives themselves and not the cooling fan on the back - inevitable when you put four fast spinning disks in a metal box. My recommendation is to get the longest Thunderbolt cable you can get and put the Thunderbay as far away as you can. Mine sits hidden away behind my desk, and while the ambient noise isn’t distracting, it is noticeable if you listen for it.

Compatibility: The SoftRAID interface does have some compatibility issues with newer hardware and software. At the time of this writing, support for the new Apple Silicon M1 Macs is limited to a beta release, and SoftRAID as a whole is not compatible with the latest version of MacOS Big Sur (version 11.2.x). Sure enough, my Thunderbay is currently totally unusable with my M1 MacBook Air, though it’s not an issue for me since I typically use the laptop while on the road. Also, if you’re a Windows user, you might be out of luck, though it does look like a Windows version of SoftRAID is in the works. Pretty big issues - but hopefully with fixes coming soon.

Update: Since the time of this writing, OWC has released SoftRAID version 6, with full support for both Big Sur and Apple Silicon. I’ve tried it on an M1 MacBook Air and it works without any issues.

Overall, though, I find the Thunderbay to be pretty much what I need in terms of managing my ever-growing library. Now that it’s all set up and going, it’s one less thing to have to think about in my overall workflow (at least until it fills up in several years - right?) and makes the whole process that much smoother. I’m looking forward to not having to worry about data capacity for awhile.